It is important during such dispiriting times to recall the infinity of small actions that support what is good in life. And it would be a mistake to dismiss their power, whether they occur in the political arena or not. What kind of effect our daily actions have at home, at work, and among our fellows will depend in part on what kind of mind we bring to the world, and this is where the heart of Buddhist teachings lie. It is not for us to calculate the impact of our “unhistoric acts”; but we can rest in the knowledge that it is through such actions that goodness is transmitted and sustained.

Early morning light

Flower vases at sunrise

Winter at the beach

Front Beach in January (2017)

Frog and Toad poems partly about Frog and Toad

Dean Rader’s collection Self-Portrait as Wikipedia Entry includes several Frog and Toad poems (“Frog Considers Slipping Toad Pop Rocks™” “Frog and Toad Confront Bashō beneath the Wreckage of the Moon”) which are staying with me.

Frog Considers a Photograph by Andres Serrano Entitled Dissection

I don’t know what this is, Frog says to Toad, who is at the stove

stirring pea soup the same color as Frog’s skin. Toad is thinkingabout beauty, which, he has just decided, is an empty bowl

a second or two before the first drops of green. Everything,Toad says to the wooden spoon, is about anticipation. He glances

at Frog who has turned the book of photographs upside downto get, it appears, a different angle. He is still looking at the

same photo. Beauty, thinks Toad, is the opposite of scrutiny.He wants Frog to put down the book and come join him,

but Frog lets out a little groan before leaning over to rest his headagainst the open pages. The book lies flat on the coffee table,

Frog’s face lies flat on the pages of the book. Toad cannot seethe photo, but it seems to be something lying flat on a table.

Toad watches Frog rise up and stare at the wall for several seconds,maybe a minute, his huge eyes as round and smooth as two glass balls.

Frog knows dinner will be ready soon but wonders if he will ever be ableto eat again or look in the mirror or listen to music or go to a doctor

or think about art. Toad likes to play a little game at this time every evening:he imagines what Frog is thinking before he gets up from the sofa

and comes to the table. He often assumes Frog is singing to himselfand tries to guess the song: “Lemon Tree.” “Rainin’ in My Heart.” “Colinda.”

“Joy to the World.” But today he knows Frog is not singing. He knowsFrog is ready for pea soup. In fact, he seems to be meditating

in preparation for dinner, perhaps even praying. Toad is so movedhe begins to sing himself and has decided to give Frog extra soup

because Frog’s reverie is one of expectation. Frog gets up, turns tolook once more at the photograph. The book begins, he believes,

to float. His eyes won’t focus. The word scalpel begins to go deepinside him. He looks over at Toad, who is cradling a pot of soup.

Frog has never seen Toad’s smile so big, and the spacebetween them is suddenly like something sliced open,

each of them waiting to see what comes next.

[Hear Dean Rader read a version of this poem]

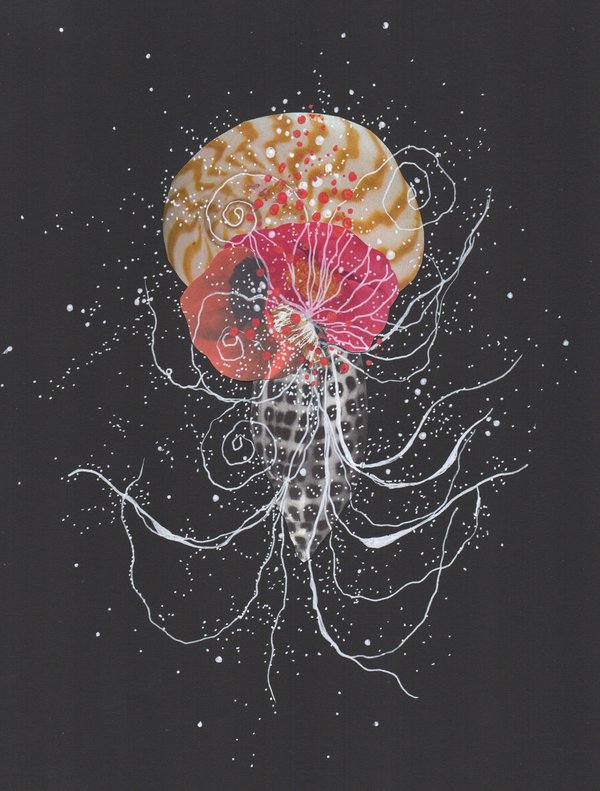

Celestial Jellyfish

Jenny Brown’s pen, ink, & collage on paper pieces are fascinating.